Adam Lippe is the Writer, Producer and Director of Wait, Wait, Don’t Kill Me, a horror–comedy about a viral pandemic in inner-city Philadelphia. The film takes place on the hottest day of the year, where an unknown virus spreads throughout inner-city Philadelphia. The infected victims, crazed by dehydration, begin attacking other residents of the neighborhood in gruesome ways. When the military is brought into contain the situation, but realize they can’t come up with a vaccine quickly enough, they fence off the area and let everyone die. A group of locals, stuck in the basement of their building, behind the fences, and separated from their family members, band together to try to survive.

The film stars Keet Davis as Gilberto Aguilar a Hispanic in his early 40’s, a garbage man, aspiring chef and father of two girls; Chandra (Noelle Figueroa), 17, and Iris (Kennedy Cill), 10. Gilberto’s married to Cheryl (Angelique Chapman), Black, late 30’s, who is a paralegal in a law office. They all live in a building with Kate (Reesa Roccapriore), a white college student in her 20’s, a newly married couple, unemployed writer, Quenton (David Marr III) and public school teacher Gray (Will Hutcheson). They are later joined by a handful of others, like a local supermarket employee (Tony Cheng), a marketing writer (Jeffrey Farber), and a grad student (Jann Punwattana).

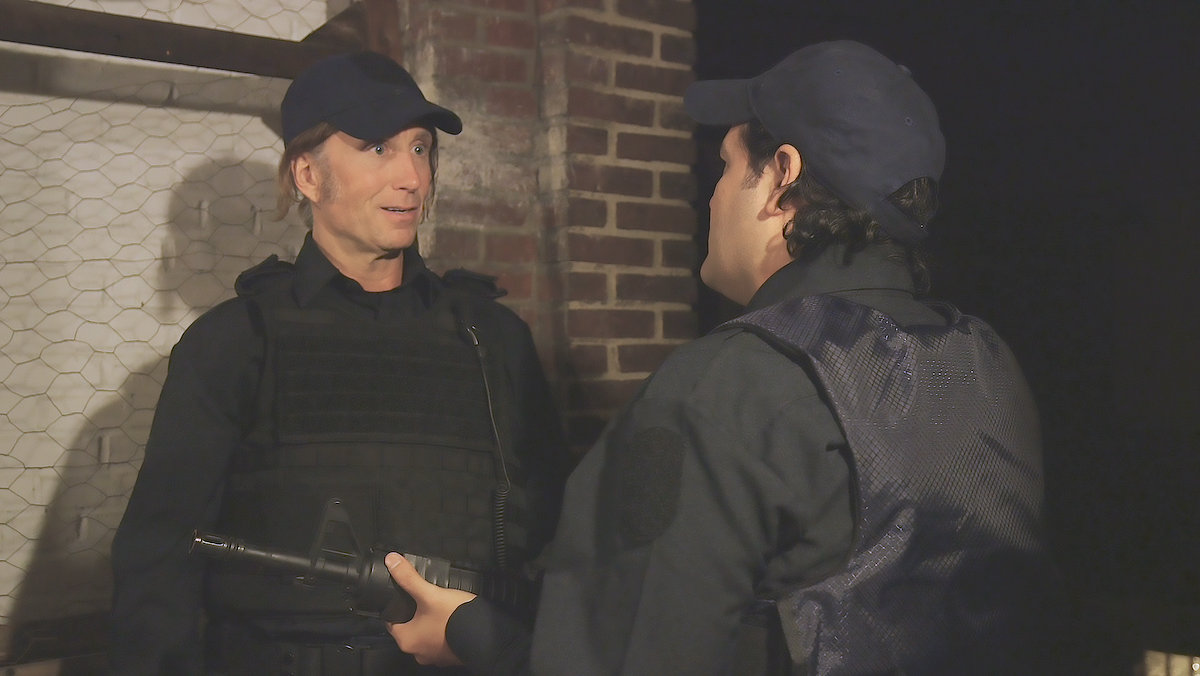

The villains, two mysterious military figures, The General (Andrew Hunsicker) and Serious Business (Preston Smith) take over the local hospital in order to stem the tide of the disease/and or exploit it for their own benefit. The film was shot by John Presutto and edited by Robert Larkin and Mark Wawrzenski, with the score composed and performed by Geoffrey Waterman. There was also a song written and performed by Cookie Rabinowitz. The animation is by Ellen Marcus.

The Official Trailer for Wait, Wait, Don’t Kill Me written and directed by Adam Lippe

indieactivity : How did the project begin?

Adam Lippe (AL) : I started the script in 2013 after a discussion with someone who mentioned wanting to make a zombie film. I told him that everyone made zombie movies, and you were better off just making a virus movie, because you didn’t have to abide by traditional zombie rules, and you could make up what the disease did and how people were affected by it.

Initially, I had a more cynical idea in mind and simply wanted to create something that was filled with all sorts of creative ways to kill people, going way over the top with the havoc and the carnage, while combining it with more realistic characters having to react to all of these absurd situations. Simultaneously, I slid in both subtle and unsubtle social commentary about the way that race and levels of poverty might be a determining factor on who, during a pandemic, might be considered more valuable by the government, and worthy of saving. I didn’t intend to direct the movie, so I just went big.

As I had been a film critic for a long time, I had seen at least a thousand horror films, and I wrote down 60 different ways I had never seen someone die in a film. The first draft, which ran a wildly unnecessary 142 pages, contained 39 of those unique deaths. It had 70 speaking parts, probably about 100 locations, and a huge amount of military and police invading the area, both killing infected people and making the situation worse.

I liked the idea of all of this chaos being just another pile-on in the main character’s lives; characters in horror films mostly just have this one thing to focus on, whatever supernatural calamity they’re dealing with. But in Wait, Wait, Don’t Kill Me, it’s like an additional annoying obstacle. So, the characters behave in less of a histrionic fashion than might be expected, considering the circumstances

But once the script was done, how do you go about getting the film made?

Adam Lippe (AL): When I was done with the script, I realized that no one else was going to make this movie. I wasn’t a famous writer, I didn’t have an agent, and the draft I wrote was unwieldy, in terms of its tone, size, and length. It had grisly horror, ludicrous action sequences (that often satirized silly moments in other action films), goofy animation to fill in exposition holes, dozens of unnecessary characters, but with a sweet family drama at its center. So, I pared it down, eliminated the big action and retained about 10 of the most memorable death scenes, and interspersed them throughout the script so the threat of violence was always present.

Right, but how did the production get put together?

Adam Lippe (AL): Production started in May of 2015 in Philadelphia, specifically Germantown, and we shot in spurts, because the intention was to shoot most of the main characters on the interior locations first, and then shoot the more sprawling horror and action later. As we had so many actors, scheduling meant we had to alternate based on availability. I also organized the schedule to make sure it followed the DP’s availability as well. I knew that since the budget was so low, the actors and crew would take other jobs in the meantime, and I had to account for that. So, we ended up shooting the first 12 days in May and June of 2015, a 2nd unit day in August of 2015, and then ran out of money. Between some footage I shot myself in September of 2015 of the Pope’s visit to Philadelphia (as I needed material that would show how widespread the fence building was in the city) and April of 2017, there was one production day. The 5 pick-up days were finished throughout 2017, and they were massively complicated scrambles, often with minimal crew, especially compared to what we had in 2015.

Editing began in 2018, but just as with production, I hired people with a lot of skill who had regular corporate jobs who would work on the film as their side projects. So each piece came together slowly. It also meant that a scene we were never able to shoot, a transitional dream sequence that was written as a buffer between a quiet dialogue scene and a scene of startling violence, had time to be designed as a fantastical animated sequence. The dream sequence, as animated by Ellen Marcus, is probably one of the best things in the movie; surreal, eerie, hilarious, and packed with so much detail that you’ll never catch it all on the first viewing.

Post-production ended just as the Coronavirus pandemic hit in March 2020, so any plans for premieres and screenings immediately evaporated. It was an unfortunate coincidence that I had a finished movie about a viral pandemic, where the government is rather indifferent to the havoc the disease Is causing in the inner city, and is simply worried about hiding the actual death count from the press, right as that actual thing was happening, and I couldn’t show the completed film to anyone but distributors. As more and more news came in, things I had written as dark comedy, about quarantines, and exploiting and hiding the disease for personal gain, became more than just prescient, but completely unnerving. As a friend who saw an excerpted scene said, “It plays like I could’ve been listening to a hot mic left on at some DC brainstorming session.” It’s now gotten to the point where I hope life stops emulating the movie because if it keeps going, we’re in real trouble.

Wow, that’s a long time to be working on the film. I have to assume there were some false starts too?

Adam Lippe (AL): My first attempt in 2014 to actually put the movie together in Philadelphia didn’t work. I couldn’t find the actors that I wanted. I didn’t realize that I had created a problem by writing a film about Germantown, specifically Nicetown, and trying to reflect the people that I saw who lived there. I had lived in Germantown, and as a white person, I wasn’t a complete anomaly, but I knew that if the film was supposed to be accurate, I couldn’t make another in a long line of screaming-dead-white-teenager horror films. So, the fact that my leads were a Hispanic man in his early 40’s and his African-American wife meant that I had to find actors who could portray that. The issue was, because no one writes movies for Hispanic men in their 40’s, there aren’t a lot of them in the industry, especially in the budget range I would be working with. It was easy to get tapes for the character of Kate, I got hundreds of them, because there’s always a deluge of short, white actresses in their early 20s. But Gilberto and Cheryl were nearly impossible to cast in Philadelphia.

So, after a few months, I gave up on casting the main roles in Philadelphia, and went to New York City to cast it and had much better luck. I thought we were going to shoot in New York, but locations proved impossibly expensive, and so I decided it would make more sense to shoot it in Philadelphia, bussing the actors in and putting them up in Airbnb’s if we had consecutive shooting days for them.

And the crew? How did you go about hiring them?

Adam Lippe (AL): I made the decision early that I wanted the best crew I could find in Philadelphia, even if their price was out of my range. I made a deal with each of them where they could read the entire script in advance of their decision. I did this all the way down virtually to the bottom of the call sheet. And if they liked the script, I thought it was more likely that they would work with me on their fee. This wasn’t a manipulative gambit; I meant it, because I know that skilled crew work on all sorts of things for the money, even if they don’t particularly like the project. I figured that if they thought Wait, Wait, Don’t Kill Me would either be fun or something they’d be proud of, they would be more amenable to negotiations.

Did you write any of the parts with particular name actors in mind? Did you approach those actors? That would probably help with the financing?

AL: I had some semi-well-known cast in mind when I wrote the script, but none of them were going to guarantee financing, they were just accurate to the parts I had written. But even at the character-actor level I was hoping to cast, getting the scripts to them through their agents was its own preventive measure. I also knew that horror films didn’t need name casts to get attention, so I felt comfortable moving ahead without it. The whole movie was its own series of long shots, with hundreds of barriers placed in our way, and the likelihood of big success was already so low, that my best bet was to foolishly barrel ahead, because I might never get another shot to make a film.

But knowing you had to keep the budget low, it must have meant that you kept cutting and cutting until it was feasible. How many drafts of the script did you do before you began shooting?

AL: The first draft was completed in early 2014, and I wrote five more drafts before we started shooting in May 2015. The shooting script was 99 pages, and the film ended up, pre-closing credits, at 96 minutes, so just about as close to a page-a-minute as you can get. The script was so dense with incident and characters, that I’m almost about as proud of the reduced running time, which is a necessity for a goofy horror-comedy like this, as am I of anything else.

Did all that paring down cause you to lose what, at least in your mind, made the script special?

AL: There were a few things about the script, besides being a genre mishmash, that made it unique. I had read many scripts over the years, and I realized that to most people, they are impenetrable. They’re supposed to function as a blueprint, but they’re rarely enjoyable to read, because of the necessary rules and structure imposed by what’s considered acceptable. I knew that since I was a nobody, there was no reason to read this particular script, and producers would likely ignore me. So, I decided to write the descriptions like those you’d find in a novel, both evocative and very, very visceral. And the dialogue was written like what you’d find in a play, sometimes chatty, rapid-fire, playful and comedic. But sometimes a character would get a lengthy monologue, filled with introspection and pain, so I didn’t have to layer in the exposition in the usual hacky ways necessary in a sci-fi/horror movie.

Did you find that approach helped get the cast and crew that you wanted?

AL: Well, it meant that when people auditioned, there was always plenty of meat in the sides; each of the main characters had at least two scenes with significant dialogue in it. So actors would audition with the first scene I gave them, and the call back would be the 2nd scene. Most of those scenes ended up in the final film, a few almost verbatim. Of course, that probably added to the length of the early drafts, but it makes the script stand out. Someone who read the shooting draft (and later worked on the film), said, “Is this a horror film with actual character development?”

That’s an ambitious way to go about it. But these seem like ways to get around writing the script in a more conventional fashion.

AL: Well, I did other things that would be considered unconventional. My other conceit in the script was something I tried to emulate from one of my favorite films, that being John Sayles’ City of Hope. That’s a film about a corruption in New Jersey, and it’s a sprawling tableau, interweaving a huge number of characters, showing how each decision from the politicians and the mobsters at the top affect everyone else beneath them. I wanted to show that the entire city in Wait, Wait, Don’t Kill Me was interwoven too, so, many times a character would say something as a button on the scene, and then we’d hear the audio from the next scene featuring different characters, as if they were continuing the conversation. So in one scene, a teacher will be talking about Egyptian staffs, and we’ll hear her say the word “staff” and the next word will from the mouth of a nurse, saying “infection,” we’d change location, and then the nurse quickly explains that she’s talking about staph infections. I did the same thing whenever there was a bit of violence, going from crunching bones to crunching lettuce. Basically, I wrote all of the dialogue and visual transitions into the script.

It was not something that I thought would be retained in the actual film; it was just a device to tie everything together, to make it feel cohesive. The thing is, we actually shot a lot of those transitions during production, and we used as many as we could in editing. Some of the transitions ended up being quite funny.

I’m pretty sure no director would be okay with the transitions being written into the script. That kind of hamstrings them a bit. It’s a good thing you directed the movie too.

AL: This was my first feature film as writer, producer, or director. I went about it entirely the wrong way. You don’t start out with a ridiculously ambitious script that, under normal circumstances, would cost $15 million. Even the completed film has 40 locations, 45 speaking parts, and 100 extras, and we shot it for nothing, and hoped it would all work out. There are many reasons this film should have never even been finished. It’s a miracle it’s even coherent, let alone well-acted and funny.

That’s a bit presumptuous, to say that we’ll find the movie well-acted and funny.

AL: You forgot coherent.

But with all the time you spent on this movie, there’s no way you’d be objective about it at this point… Before you made Wait, Wait, Don’t Kill Me, had you made any other films? If you did, how did that experience help you?

AL: The last thing I made was a 15-minute short in college back in 2000. I haven’t looked at it since then, but like Wait, Wait, Don’t Kill Me, it was a melange of ideas and tones. It was overstuffed too, and it was both achingly sincere and abrupt. Jeez, maybe I haven’t learned anything.

If that’s the case, how is your film different from the hundreds of other low-budget independent horror films released every year?

AL: The level of craft. When people first see the movie, they’re surprised that it’s a real movie with real actors, that the score is excellent, that it’s well shot and it sounds good, the make-up is effective, and that it’s seemingly so large in scope. Of course, as soon as that reality sets in, they stop grading on a low-budget curve and then you have to compete against more traditionally respectable fare. Because of the level of skill of my cast and crew, I didn’t have to do so much hand-holding, which you do have to do when you’re making shorts in college. I’m also calmer and more collected on set (the stress on the inside is rarely evident), and able to express my thoughts in a more concise manner. It means that when a problem arises, I’m much more likely to come up with a variety of solutions, as opposed to panicking that the scene isn’t going exactly as I pictured it.

What kinds of problems arose?

AL: It was more about how we avoided those obvious problems. Once we got down to the point where we had a minimal crew, basically all of 2017, that’s where meticulous planning became necessary. That way, if there needed to be a change last minute on set, I was prepared and I could adjust. There was a pick-up day where we had to shoot 18 sequences in 10 locations, with 15 actors, in less than 12 hours. It involved cast and crew coming in from Delaware, New York City, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The crew that day was two camera operators, one boom operator, one driver taking people back and forth to the bus station, one producer putting out external fires, and me, functioning as writer/producer/director/script supervisor/assistant camera/assistant director/property master/make-up. In between takes, I would order bus tickets for the cast so they could get home to New York. We even snuck in some on-location ADR with three of the main actors that day, which was recorded while one of the locations was being lit.

Financial necessities meant that we had to do this sort of day more than once. All of the necessary footage ended up in the movie and none of it looks rushed or sloppy.

Yikes. That sounds exhausting.

AL: I think the key is that there was every reason to stop making the film and I just kept going, especially during that nearly 18-month period between shooting days. The financial toll, the emotional toll, the physical toll it took on me (and not just my hairline) was enormous. But I couldn’t just have it be an unfinished project. That would have been a nightmarish regret that would have been worse than the sensible thoughts I was constantly having about what the film was doing to my mind, my wallet, and my body.

With all that work, though, it seems like getting to the finish line was the real accomplishment. But that obviously wasn’t the point. What do you want the audience to get from the film?

AL: It’s essentially a dark comedy in the guise of a horror film. It’s goofy, silly, serious, absurd but not self-aware, and occasionally very pointed, and, for some reason, kind of sweet. It’s basically designed for people to go along for the entire ride and enjoy its rambunctious nature, or tune in and tune out for the things that appeal to them. I think filmmaking, while obviously very collaborative, is, especially at this level, a purely self-indulgent act. And if you agree with that premise, then Wait, Wait, Don’t Kill Me has completely succeeded.

Seriously?

AL: As with any filmmaker, I hope people are entertained and have something to think about later. But I’d be okay with just about any reaction including anger, frustration, and irritation, all of which are better than the audience being indifferent.

Where can people see the movie?

AL: The film premiered on August 21st, 2020. It was screened virtually via The Colonial Theatre in Phoenixville, PA. That means you can see it at home right away. Buy a Ticket and begin watching now!

What are you working on now?

AL: I had wanted to shoot a script in the fall, much smaller, with a cast of 3 and mostly on one location. But who knows when we’ll safely be able to shoot anything again? The script itself is something that I’ve been working on in various forms for more than 15 years, sort of a mix of Oleanna and Oldboy. And with the experience I now have from Wait, Wait, Don’t Kill Me, I know how to shoot it quickly and inexpensively. But until it can be determined what happens if one of your actors or crew gets sick, how you can get something insured, or even, after the inevitable recession, what distributors will even be around to rip me off, it’s hard to know when I’ll actually be able to shoot it.

Anything else you want to add?

AL: I just want to briefly talk about distribution. I did tons of research on how to find the right distributor, what the pitfalls were, who to avoid, and all the various other options like aggregators and self-distribution. I stayed up to date, knowing that these things change by the week, with new companies popping up, old companies turning into places that are desperate and rip filmmakers off, while also learning all the new terminology (minimum guarantees, AVOD, SVOD, TVOD, marketing minimums, etc.) and different types of platforms.

But what I’ve never seen in the last few years, at least on a very low budget (say, under $100,000), is a success story. No one who broke even. [If they did, they didn’t pay themselves.] No one who even got close. Lots of people getting ripped off and with sad stories to tell. Certainly, no one who could make a legitimate living off of their films. I spoke with more than a hundred filmmakers in the past year, regarding strategies and experiences and all I’ve seen are a lot of dashed hopes and not much else. If you grossed $5,000 on a film, you did well. And it’s not that all of these filmmakers are making huge mistakes, or going with distributors who are going to rip them off. There are no options. There is no pathway. It’s a lot of people lying to themselves because that’s the only way they can grin and bear it. It’s self-preservation. And it’s a totally understandable reaction.

That’s sobering.

AL: Well, no one should ever talk to me and expect to be uplifted. Or expect a short answer.

Tell us what you think of the interview with Adam Lippe. What do you think of it? What ideas did you get? Do you have any suggestions? Or did it help you? Let’s have your comments below and/or on Facebook or Instagram! Or join me on Twitter.

Follow Adam Lippe on Social Media

Website

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Richard Green Documentary, ‘I Know Catherine, The Log Lady’: Premiere in NYC, LA May 9th

Lynchian Doc I Know Catherine, The Log Lady Makes Hollywood Premiere 4/17, Rollout to Follow

In Camera by Naqqash Khlalid Launch on VOD April 29

Naqqash Khlalid’s Directs Nabhan Rizwan. In Camera stars an EE BAFTA Rising Star Award Nominee.

2025 Philip K. Dick Sci-Fi Film Festival Award Winners Announced

Vanessa Ly’s Memories of the Future Awarded Best PKD Feature

Dreaming of You by Jack McCafferty Debuts VOD & DVD for April Release

Freestyle Acquires “Dreaming of You” for April 15th Release

Hello Stranger by Paul Raschid set for London Games Festival & BIFFF

The film Is set for an April 10th Premiere at The Genesis Cinema in London (LGF) and BIFFF

Daydreamers Official Trailer by Timothy Linh Bui: Released by Dark Star Pictures

Daydreamers Vietnamese Vampire Thriller – May 2nd release